Parish Life in the Thar Parkar Desert

The Thar Parkar Desert is situated in the southeast of Pakistan in Sindh province. It covers an area of 22,000 square kilometers with an estimated population of 1.5 million people and is one of the most densely populated deserts of the world. It is a place of beauty, especially after the monsoon rains at least. Columban Fr. Tomás King provided this update about his parish in the Thar Parkar desert.

in Pakistan since 1992.

The Thar Parkar desert has an interesting geology. There are red granite hills with deep gorges which are home to a rich variety of flora and fauna. One of the trees found in the area is the Gugral tree, which is the tree that provides the resin from which incense is made. It is estimated that 70% of the trees have dried up due to criminal groups extracting its resin using poisonous chemicals to speed up the process of extraction in order to sell the resin in greater quantities in the markets of the big cities.

There are springs associated with Hindu shrines, rituals and pilgrimages. Hindus and Muslims visit them in large numbers on special occasions. There are a number of Jain temples, some dating back to the 14th century, when the Jains were prominent in the area.

Nagar Parkar is a small town within a few kilometers of the Indian border. It is considered the homeland of the Parkari Kohlis, one of the many low caste tribal peoples to be found in Sindh. There is a parish center in the town which has been administrated by Columbans since the mid-1980s. There are less than 100 Catholic families, and they are scattered over a large geographical area. It is the only area in Pakistan where more than 50% of the population is Hindi. The area also has white china clay deposits which are being mined. But for the most part Thar Parkar is an arid and semi-arid desert, where, underneath its sands massive amounts of coal have been found and large-scale mining is being planned.

The land is fertile when sufficient rains fall. Production of crops depends on the monsoon rains which should fall from mid-June to mid-August each year. Unfortunately, for the last ten years there have been drought conditions in Thar Parkar. Due to this many people migrate to the interior of the Sindh province in search of work, food and water. In 2014 it was estimated that 470 people died due to drought, mostly children. But that is only the official number. Along with human deaths there were thousands of livestock deaths, which are vital to the economy of the desert people.

Obviously water is a serious issue in this area. Surface water is minimal, found in artificially dug depressions. Small dams and reservoirs are being built by the government and some non-government organizations (NGOs) to capture and store rainwater when it does fall. As regards ground water, studies show that there is what is called aquifer zones at varying depths, including in the areas where coal is located. Some of this water is harvested through digging deep tube-wells for drinking and household use. What will happen to this water with the coal mining? For the mining itself, massive amounts of water will be necessary.

Pakistan does not produce sufficient power to provide electricity for all its peoples’ needs. “Load shedding,” where electricity is cut off for hours on end every day, is a part of life even during the hot summer months when the increased demand is not met. It is not unusual to have protests that sometimes turn violent, as people vent their frustration and anger at prolonged load shedding.

In such a context the discovery of massive amounts of coal under the sands of the Thar Parkar Desert, which has the potential to end load shedding and provide for all of Pakistan’s energy needs for generations to come, is seen as a Godsend. But at what cost to the desert environment and its people today, and to future generations? Will there be more prolonged droughts in the Thar Parkar Desert, as well as the heavier monsoons and increased flooding in other parts of the country?

The government and some mining companies, including a Chinese company, have begun the process of extracting the coal. China’s presence reinforces its policy of seeking out natural resources from virtually anywhere in the world to feed its own domestic needs. Presently the road is being upgraded from the main extraction area to Karachi, a distance of almost 300 kilometers. Small towns are being by-passed. So any so-called economic benefits will be for the big cities and China, with little for the poor of the desert, except contaminated water!

All of this is happening as Pope Francis has recently released the encyclical Laudato Si in which he says climate change is a moral issue. He endorses the science that says humanity is a major contribution to the ecological crisis facing planet Earth. A major part of that contribution has been the burning of fossil fuels. He writes: “A very solid scientific consensus indicates that we are presently witnessing a disturbing warming of the climatic system…. The problem is aggravated by a model of development based on the intensive use of fossil fuels, which is at the heart of the worldwide energy system…. We know that technology based on the use of highly polluting fossil fuels – especially coal, but also oil, and, to a lesser degree, gas – needs to be progressively replaced without delay…. Access to safe drinkable water is a basic and universal human right, since it is essential to human survival and, as such, is a condition for the exercise of other human rights….”

This is a microcosm of the challenge facing humanity. How to provide the energy necessary while decreasing the dependency on fossil fuels? The planet cannot tolerate the extraction of the vast quantities of coal in the Thar Parkar Desert and other locations around the world. It highlights the extent of the conversion and change of life style that is necessary to turn things around.

It is also a missionary challenge facing the local church, and a challenge for the many NGOs who claim to be working for the betterment of the people. It is a big challenge in the presence of a myriad of many other challenges.

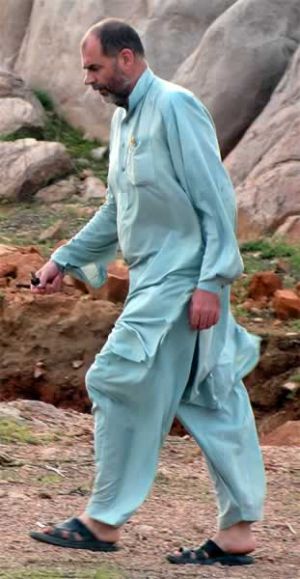

Columban Fr. Tomás King (pictured above) has been a missionary in Pakistan since 1992.