Tales from a Communist Prison

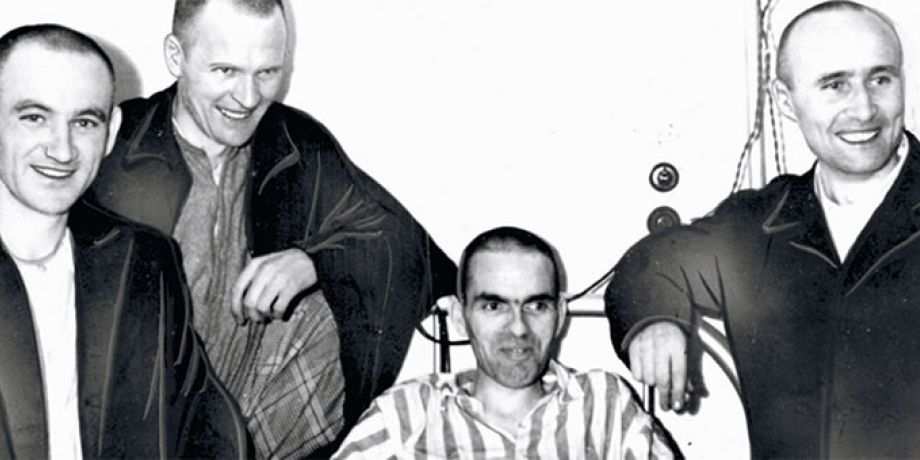

Four Columbans, John Casey, Patrick Ronan, Owen O’Kane and Patrick Reilly, all attached to the Huchow mission in the Chinese Province of Chekiang, were arrested by the Communist authorities on the same day in 1952. Transferred to Kashing jail, they spent the next sixteen months in solitary. Here are some extracts about their experiences, as related in the book, But Not Conquered.

Fr. John Casey:

Consolation and Companions

The prison in Kashing turned out to be the old Kuomintang jail and that first night I was the only prisoner in it. Next evening I heard a second prisoner being led in. He had a very long step and peeping out I saw that it was Fr. Owen O’Kane. Five minutes later Fr. Paddy Reilly arrived, very lame with beriberi. The following evening Fr. Paddy Ronan was led in. I was delighted to see the other priests arriving; it would be such a consolation for us to be together. I was to be held in that jail for nearly sixteen months. We were in separate cells. My cell was six feet by six feet.

In mid-January I got dysentery and had it on and off until I was released. In February, I felt for the first time a tingling pain. It was beriberi, a disease of malnutrition. I experienced a swelling of the legs and severe jabbing nerve pains especially at the joints, toes and fingertips. By May I was at my worst and must have been under 100 pounds in weight. I used to pray a good deal in jail and found it easy to pray; I was always certain that I was being prayed for by others. Doctrines like the Communion of Saints and the Mystical Body of Christ became very comforting to me. For the first time in my life I learned the meaning of happiness in suffering.

In mid-January I got dysentery and had it on and off until I was released. In February, I felt for the first time a tingling pain. It was beriberi, a disease of malnutrition. I experienced a swelling of the legs and severe jabbing nerve pains especially at the joints, toes and fingertips. By May I was at my worst and must have been under 100 pounds in weight. I used to pray a good deal in jail and found it easy to pray; I was always certain that I was being prayed for by others. Doctrines like the Communion of Saints and the Mystical Body of Christ became very comforting to me. For the first time in my life I learned the meaning of happiness in suffering.

On November 24, 1953, we were formally condemned and expelled from China forever. It was the first time I could see the other three priests face to face, and I was shocked at how ill and weak they looked. During my seventeen months in prison I had felt serene enough; the judge had pretty well convinced me that I would be in prison for life and I was resigned and happy. But, at the end, the prospect of immediate freedom nearly drove me insane.

Fr. Patrick Ronan:

Signs and Sermons

The first thing I noticed on being transferred to jail in Kashing was a big pair of boots on a window-sill diagonally across from my new cell. “They surely belong to no Chinese,” I thought to myself; shortly afterwards I heard voices raised in argument about water. I peeped out and saw Fr. Paddy Reilly with a shaven head and a little beard arguing with a guard. He didn’t look towards me, but I knew he’d seen me out of the corner of his eye. Once the guard moved along, Paddy and I promptly popped up to our windows and in sign-language we held a quick exchange of greetings, congratulations, encouragement … and absolutions.

I cocked my ears to interpret every sound. Coughing from a cell across from me, and not so very far away, plainly said, “Welcome, Paddy, I’m here too; chin up!” – that was Fr. Jack Casey. A cough from the far end of the corridor was Fr. Owen O’Kane. For ten days Fr. Paddy and I were left in these two cells where we could see each other. Between visits of the guards we traded information about fellow-priests – we just imitated some idiosyncrasy of each. One of the first things was a code for absolution; two hard nose blows meant a request for absolution; a responding cough meant that it had been given.

We first made jail rosary beads in August 1952. On communist feast days (Labor Day, Russian Revolution Anniversary, etc.) we got better food which included Chinese steamed bread. From this I made my beads. I steeped the bread in water until it became pasty and then I molded the beads around an old string pulled from a quilt and left them to dry. For the crucifix I cut off a piece of leather and trimmed it to the proper shape. I then formed the figure from rice squeezed into a paste and attached it to the cross by small pieces of wire. Those beads journeyed all the way to Hong Kong and to freedom with me.

Fr. Owen O’Kane:

Keeping Sane

The seven weeks that I spent in Tehtsing (my local jail), in an overcrowded cell, with constant interrogations, were truly dreadful. When I was moved to Kashing I had the doubtful luxury of a cell to myself. At first it was a tremendous relief, and there was of course the immense consolation of being close to three fellow-Columbans. But then I discovered that solitude has its own dangers for the mind. With nothing to occupy me, my mind constantly went back to nights under a dazzling lamp and the questions that kept coming until the brain cried out for a rest always denied. I set about convincing myself that my mind was normal. “You are sane, you are sane!” I found myself repeating to myself.

After my illness (beriberi) I wondered how I could get my strength back. I could not bear to put a hand on my chest — it was like rubbing naked bone. When I wanted to rise I had to do so in stages. Initially I practiced kneeling — a fall from this half-way posture was less dangerous. After that I practiced leaning upright against the wall, and this way I got back to my feet again. I have painted, I fear a grim picture of life in a Chinese Communist jails; before I end I want to add that out of my fifteen months I can only remember two days on which I was unhappy. One was Christmas Day 1952, for my thoughts tore loose from their narrow moorings and sped in spite of me to Ireland, Antrim and home.

Fr. Paddy Reilly:

Losing My Sight

One morning in January 1953, I woke up to discover that I was completely blind. A doctor examined my eyes. He shone two torches into my eyes and still I could see nothing. I heard the doctor report that my eyes were in a particularly bad condition because of prolonged beriberi; it was practically certain that I would never see again. The guards tried to persuade me to confess “my crimes” and that I would be released to the best of medical care. I replied, “I have committed no crimes and I will never confess that I have. Never!”

During the next few days I was given some tablets and an injection. I prayed to Our Lady with great confidence and simplicity. Three days later I woke up and could vaguely distinguish the bars on the windows.

On March 12,1953, guards came to my cell and led me out through the town to the hospital. I had been very ill with beriberi all through the winter, and the Communists decided apparently that I must have medical care. On my third day, when the guard had gone outside for a moment, a woman rushed into the room.

“You are a priest? Don’t worry I’m a nun. Do you want anything?” “Yes, I replied, “Could you get me Holy Communion?” She ran out of the room without replying. A few days later, one of the nurses was loitering at the door. She made a scene, chiding the guard for the state of his bed, then came over to do the same to me but took a pyx out of the pocket of her apron and put it under the blanket. The date was March 17, St. Patrick’s Day: it was a precious gift from my patron.

Adapted from But Not Conquered by Columban Fr. Bernard T. Smyth (ed), Section III, Brown and Nolan Ltd, Dublin, 1958.