My mind was significantly shaped by mathematics, logic and informal debate. Thinking things through, stating a position and articulating the case for a position has been constant in my life. For some, the primary way of learning and communication is in the context of conversation. Such people learn by engaging with others, speaking and listening. They yarn, tell and listen to stories. Such stories may simply be about life experiences or they may be stories that interpret the meaning of things. However, my experience of life tells me that there is another primeval pattern of learning, thought and insight that might be potentially operative in all of us.

I recall an occasion when I was sitting in a chair, next to the altar in a busy and noisy church at the end of Mass. I was resting and watching men and women buzzing about organizing the removal of a large portable platform on which they carried the florally adorned image of their patron saint. It must have been clear that I was enjoying myself as one of women said to me: “Padre, you seem to like the people’s religion.” I was unfamiliar with the implied distinction between the priests’ religion and the people’s religion.

I recall an occasion when I was sitting in a chair, next to the altar in a busy and noisy church at the end of Mass. I was resting and watching men and women buzzing about organizing the removal of a large portable platform on which they carried the florally adorned image of their patron saint. It must have been clear that I was enjoying myself as one of women said to me: “Padre, you seem to like the people’s religion.” I was unfamiliar with the implied distinction between the priests’ religion and the people’s religion.

In that framework, leading the celebration of the Eucharist was an integral part of the priests’ religion. Organizing and participating in the festivity in honor of the patron saint was similarly part of the people’s religion. In the Eucharist there is both teaching and celebration and while the “people’’ are the vast majority of those present, the priest leads both the teaching and ritual parts. On the other hand, the celebration in honor of the saint is entirely in the hands of the devotees. There is no teaching but much ritual and music; there may even be fireworks. There is a procession, then a party with food and drink, music and dance, and, of course, much camaraderie. There is no strictly defined ritual, but there is ritual, understood and enacted by various designated members of the community as they celebrate their patron saint’s feast day. There is intense communal activity and sharing.

I remember that I engaged with the woman who commented on my liking the people’s religion and told her that, yes, I did like the people’s religion, which took me back to an occasion when I had joined in a celebration of the people’s religion.

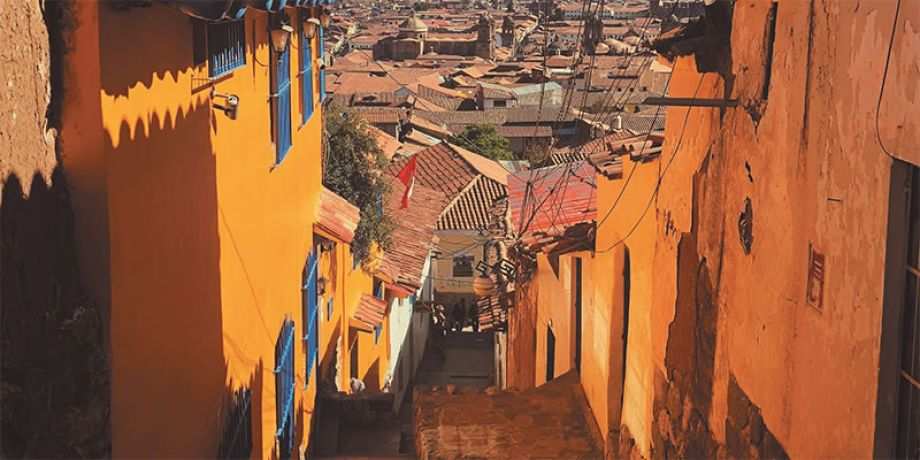

That had been in another parish, in the upper part of a valley rising up towards the east from the coastal plain, much of which is now covered by the suburbs of Lima (Peru). In this part of the parish, there were, at that time, around 500 houses, some in a ring around the edge of the valley wall and others in a few short, crisscrossing streets in the center of the valley that had been levelled at the time of the original settlement. The residents had squatted in that part of the valley and then negotiated an agreement whereby they became owners of the land.

A small group in the local community had a special devotion to El Señor de los Milagros (The Lord of Miracles). They wanted to carry an image, in this case, a painting, on a portable platform (el anda) around the streets of the settlement (el barrio). There would normally be a band to accompany the image, rotating teams to carry the portable platform and any number of devotees. Our route was the unpaved street that looped around the edge of the top part of the valley floor. We struggled to find a few women to carry el anda as no men had come along. There were more dogs than people and some children joined in too. There was no band so someone found a cassette player with batteries that ran out during the procession. For the most part, neighbors watched respectfully as the procession passed their house but there was some jeering. I tagged along, taking things as they happened and not feeling in any way responsible for trying to “fix” anything.

It occurred to me at some stage of the procession that the small ragtag group of people and mangy dogs, walking slowly, until the batteries ran out, to the canned music of a few hymns was God saying to the people of the barrio, “I am with you.” There was no sewage system installed and no piped water. The houses were small and mostly unfinished – some of brick and concrete, some of adobe (mud and straw brick) and some of matting made from sugar cane (esteras). The residents were poor, very few with more than primary education and most struggling to find or hold a steady job. Some were desperately poor.

I have no idea why it occurred to me that we, on the initiative of a small community group, were in fact announcing God present in that community. There was nothing particularly beautiful about our procession. In fact, it probably seemed a little crazy to most of those watching. No one was making any promises about anything. At that time, we had not acquired land to build a chapel. There was no local church organization up and running. No one had ever told me that announcing God’s presence was the basic purpose of such a procession. I was just wandering along with the small group chatting and, for moments, wondering about it all. I had no expectations. In fact, in a certain sense the whole business seemed to be a disaster from beginning to end. And yet, it ended up being one of the most memorable moments of my life.

The key to insight in this case was not related to reading and thinking, not even to listening to someone speaking wisely, but simply being with a group of people going about expressing their faith in God in a way that was familiar to them – people’s religion!

After many decades on mission in Peru, Columban Fr. Peter Woodruff now lives and works in Australia.