Tradition has it that Saint Maughold, Patron Saint of the Isle of Man, was a contemporary of Saint Patrick and a forerunner of St. Columban.

On a recent Columban promotional visit to the Isle of Man I chanced upon a line of holy statues outside the Catholic church in Ramsey. I recognized all the images apart from one, a small empty boat. “That’s the sign of Saint Maughold, co-patron of the parish and patron saint of the whole Isle of Man,” explained Fr. Philip Gillespie. When not attending to his duties as Rector of the Beda College in Rome, Fr. Phillip helps serve the Catholic population on Man, and is well versed in the island’s culture. He went on to relate the tradition of St. Maughold (normally pronounced “Makeld”).

When St. Patrick arrives in Ireland he comes across this brigand and freebooter called Maughold, who eventually repents of his evil ways and confesses his sins to the Saint. Patrick pardons him, but as a penance pushes him out in a coracle with neither sail nor oars, saying, “wherever you land will be your place of mission.”

Eventually, he makes landfall on the Isle of Man, just down the coast from Ramsey at what is called St. Maughold’s Head. The castaway drinks from a spring (still known as “Maughold’s Well”), and then stumbles upon two Irish monks (earlier disciples of Patrick) who have founded a small monastery nearby. Maughold joins them, later becomes abbot, and is finally invited to be Bishop of the Isle of Man in around A.D. 500.

Whatever the historical truth of the tale might be, the fact is that by this time Irish missionaries HAD succeeded in converting the inhabitants of the island (thereafter known as the “Manx” people) to Christianity. Moreover, this venture was just a small part of the great missionary wave which would carry Irish monks to much of northwest Europe, be it Columba (“Columcille”) to Iona in Scotland or our own St. Columban (“Columbanus”) to France, Switzerland and Italy.

Fr. Phillip filled me in on a little more of Isle of Man’s story. Incidentally, the name “Man” has nothing to do with gender! It probably comes from “mannin,” a corruption of the Celtic Manx word for “island.” Sitting as it does more or less equidistant from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, the territory was considered fair game by any potential invader during the Middle Ages. It fell prey to the Irish in the 5th century (not all those visitors from Ireland were peace-loving missionaries, apparently), followed by the Anglo-Saxons in the 7th century, the Vikings in the 8th, the Scots in the 13th, and the Normans in the 14th, each successive invader leaving its mark on the local culture and landscape.

As a result, the Manx have developed a distinct identity. They’ve struggled to maintain the Manx language (akin to Celtic Irish). This has enjoyed a post-War revival (encouraged by, among others, Irish President Eamon de Valera) and is now spoken by almost 2,000 of the island’s 84,000 inhabitants.

By early modern times the Isle of Man was effectively part of Great Britain. However, in recognition both of the island’s loyalty and its individuality, in 1866 Queen Victoria declared it to be a Crown Dependency, subject not to Parliament but directly to the monarch. Hence, the Isle of Man is NOT part of the United Kingdom. It does NOT send representatives to the Westminster Parliament, instead maintaining its OWN Parliament: the “Tynwald.” Reputedly, the Tynwald was established by the Vikings in 979 A.D. and is claimed to be the oldest continuous representative institution in the world. It did not take part in the 2016 Referendum on E.U. Membership. Consequently, some Manx legislators argue that Brexit does not apply to the Isle of Man!

Intrigued by all this, I decided to visit the site of St. Maughold’s Monastery. It is a deeply evocative place. Fr. Phillip had already warned me that, “when you hear the term ‘monastery’ you tend to think of some big, organized institution, but no, Celtic monasteries predate this, they are quite different. They started off as collections of huts – ‘keeills’ in Manx, ‘cells’ in English – with a monk alone in each little building, where he’d eat, sleep, pray and even be buried when he died.” At St. Maughold’s you find the remains of four such structures. One has had an ancient church built over it and dedicated to St. Maughold, leading people to claim that the very remains of the saint lie within.

However, the real treasures are to be found dotted around the site, in the form of gravestones which span some fifteen centuries. Their designs reflect Manx, Irish, Saxon, Viking and Norman influences, with the inscriptions varying from Latin and Old English to Ogham Script and Norse Runes.

I refreshed myself at St. Maughold’s Well. The local Anglican church still draws its baptismal waters from the spring, a moving example of Manx adherence to tradition.

Finally, I scaled the summit of St. Maughold’s Head. Looking out to where the currents of the North Atlantic churn into those of the Irish Sea, I imagined I could spot Maughold, tossed about in his tiny oar-less craft, approaching the shore to evangelize a people and inspire an island.

Columban Fr. John Boles lives and works in Britain.

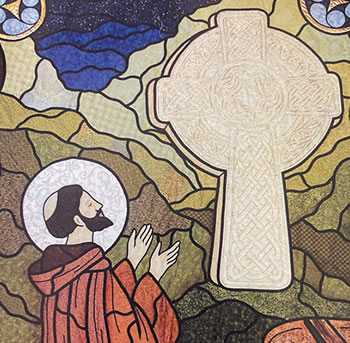

The Lonan Wheelcross

Situated amidst the remains of another ancient “keeill” monastery a few miles south of St. Maughold’s, the Lonan Wheelcross is the finest Celtic monument on the Isle of Man, and one of the best preserved “in situ” Celtic crosses anywhere in Europe. Dating from the 5th century, it is decorated with intricate interlacing and displays the characteristic Manx detail of four circular hollows at the junction of the shaft and arms.