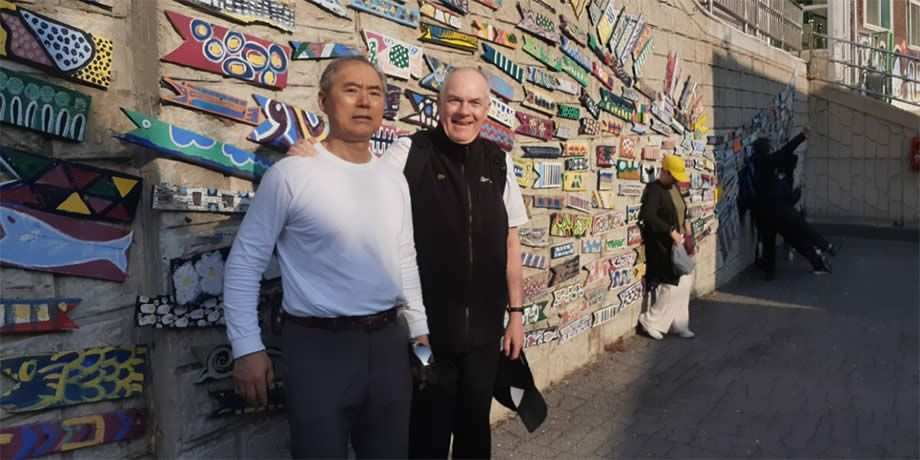

Between them, the lives of long-time Columban supporter Pelagio Lee and his father span the whole drama of modern-day South Korea. Their story hinges on a former refugee settlement-turned-tourist attraction. Pelagio told Columban Fr. John Boles all about it as they walked the lanes of “Gamcheon Culture Village.”

Gamcheon is a special place. As the top tourist destination in South Korea’s second city of Busan, it has been variously dubbed “Korea’s Santorini,” “Busan’s Machu Picchu” and “Asia’s artiest city.” Each day visitors both national and foreign stroll through its winding, narrow hillside streets, admiring the striking murals and pastel-colored houses. In pre-Covid days, this “culture village” was welcoming over a million tourists a year.

But the pretty facades of Gamcheon belie the fact that it was born out of tragedy. Tremendous events have taken place here, producing some extraordinary people. Columban supporter Pelagio Lee Dong-hwa and his father, Lee Gyu-tae are two of them. Together, their lives tell in microcosm the dramatic tale of modern-day South Korea. Pelagio unfolded the tale as he led me through Gancheon’s labyrinth of picturesque alleyways.

His father, Lee, was born in 1908, just at the time when Korea was falling under Japanese control. Resistance against the Japanese took many forms, one of them being the emergence of a uniquely Korean religious movement known as “Taegeukdo,” influenced by Buddhism and Confucianism, but markedly national in character. Mr. Lee joined this religion and soon became one of its leaders. The sense of patriotic, spiritual identity enabled the movement’s adherents to withstand the rigors of Japanese occupation and the Second World War.

However, just five years after the liberation, a sterner trial came as North Korea invaded the South in June 1950. Mr. Lee and his co-religionists joined the flood of refugees as it poured southwards towards the only enclave holding out against the communist army: Busan. Here, an international force mandated by the fledgling United Nations resisted the onslaught until relief arrived, and the Allies under legendary General Douglas MacArthur succeeded in repulsing the invasion.

The war ended in 1953, leaving an appalling legacy with around three million dead. Busan was the only city in the country that hadn’t been devastated, so the leaders of Taegeukdo decided to make this their permanent home. Pelagio’s father went to work with a will. On the edge of the city at the foot of a mountain, he built a temple and a simple dwelling, then helped group the pathetic huts of his congregation into serried ranks along the contours of the hill, rising ever upwards. Thus, Gamcheon came into being.

The rows of shacks took on a remarkable sense of order, with no one roof blocking the view from the dwelling behind. As the economy improved and South Korea began to enjoy its miraculous “Asian tiger” boom, people progressively improved their houses, with the colorful painting scheme going on to inspire eventual “culture village” status. Pelagio was born here in 1959, in the simple family home next to the temple, one of ten children. He told me how he has mixed memories of his father (who died in 1980). “He was a just man, but remote,” he recalls, “very patriarchal, like someone from the Old Testament. I’m sure he loved me, but he found it difficult to show it.”

Maybe this was why Pelagio, when he grew up, declined to follow in his father’s footsteps in the Taeguekdo movement. Nevertheless, he HAD inherited Mr. Lee’s passions for the Divine, social justice and compassion for the poor. He began a spiritual search, which continued through his high school days and training as an engineer, and came to a surprising conclusion in – of all places – the army, during his military service. One day, in the barracks he came across a Catholic catechism. As he put it, something within him “connected.” He felt he’d found what he was looking for.

Another feature of South Korea in the years following the Korean War was the rapid growth of Christianity, in which the work of Columban missionaries featured prominently. Pelagio was part of that great post-war flowering of the Church. Now a baptized Catholic (and, on leaving the army, a policeman!) he joined a parish in his native Busan and became one of its volunteer workers. Feeling God might be calling him to be a priest, he tested his vocation, first, with his local diocese and, later, with the Columbans at our seminary in Ireland, before realizing that his true vocation was in a secular role at home.

Back in Busan and employed as an engineer, he offered his services at the cathedral to an outreach program for Filipino migrants, putting to good use the English he’d learned with the Columbans. He found himself working alongside a teacher, Cecilia Kim Hae-jong, who proved to be the love of his life. They married in 2008.

I’ve known Pelagio ever since we were in the together Columban seminary at Maynooth in the 1980s. If there is a sincerer Christian and Catholic in this world than Pelagio, I don’t know who it is. Now approaching retirement, he reflected on his life and God’s kindness to him. “I’ve met so many good people,” he told me, as we wandered through the lanes of Gamcheon. “When I have a difficult time, God always sends someone to help me. I remember this sergeant in the army. Then there were a Chief of Police, a Sister in the parish, and a Columban priest in Seoul. Cecilia, of course.”

He doesn’t mention his dad. Yet I can’t help thinking that the qualities which shone through Mr. Lee Gyu-tae – as he transformed a refugee camp into a home for thousands – have shone with equal brightness through the life of my dear friend Pelagio.