Commitment to Christ

"You are mad to try to organize a foreign missionary society while Ireland is in the throes of a World War," was the warning which met Fr. Edward Galvin, just returned to Ireland after four years work in China. He and Fr. John Blowick, a very young professor of theology at Ireland's national seminary in Maynooth, were working together for that very purpose in that summer and autumn one hundred years ago. Driven on by the need they felt for missionary priests in China they counted on God's favor and ignored the voices of caution.

Awakening a Missionary Consciousness

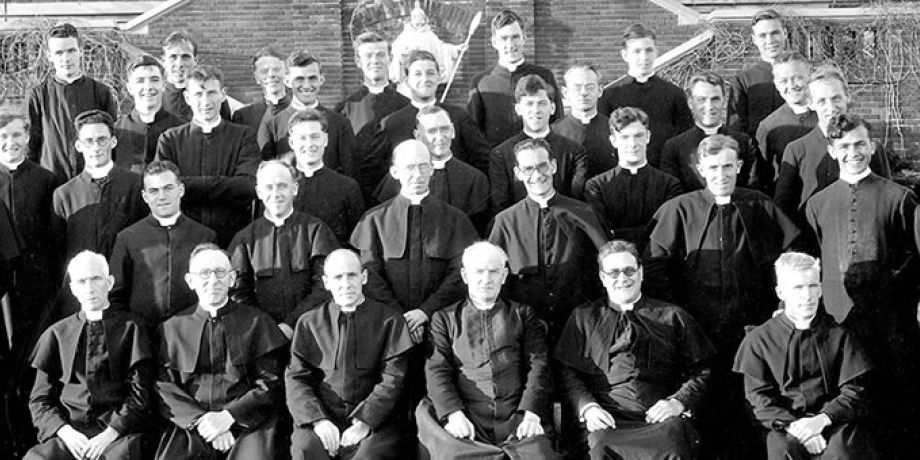

On October 10, 1916, the bishops of Ireland gave permission for the founders of the Maynooth Mission to China (afterwards known as the Missionary Society of St. Columban) to begin recruiting and collecting money to send Irish missionaries to China. Frs. Galvin and Blowick launched a monthly missionary magazine, The Far East, in Ireland in 1918 to gain the support of the Catholics of Ireland for the new Society and its activities.

There were early indicators of success. The Far East had a circulation of 45,000 in 1919. By 1921, priest volunteers numbered 50 and seminarians 88, and over 150,000 pounds had been collected from the people of Ireland for the mission.

Church historian, Colm Cooke comments that "For the awakening of missionary consciousness at a national level and an increasing commitment on the part of the Irish church to the missions, the foundation of the Maynooth Mission to China was of paramount importance." In the 21 years subsequent to its founding, four other completely missionary societies were formed in Ireland to work in Africa and Asia. By 1976 there were 5,803 Irish missionaries working in Africa, Asia and South America and at least another 5,000 Irish priests and religious in the English speaking churches. The missionary movement in the Catholic Church in Ireland developed phenomenally in the twentieth century.

The Easter Rising

A few months earlier, on Easter Monday, 1916, a small force of poorly armed Irish volunteers took over the general post office and other strategic buildings in central Dublin and declared Ireland a free and independent Republic. The superior numbers and fire-power of the British army quashed the movement by the weekend.

Pearse, and other insurrection leaders, drew inspiration from their religious beliefs for an armed rebellion, which they realized would have little chance of success. They believed that their blood sacrifice would inspire a renewed nationalism in the whole country. Britain's preoccupation with the Great War seemed to them to offer an opportunity.

The public reaction in Ireland was overwhelmingly against the rebels and several bishops condemned the rising on Sunday, May 7. However, by May 14, fifteen of the rebel commanders had been executed, and the mood of the people began to change. During Easter week the rebel garrisons had frequently recited the rosary together. A historian said, "Even those churchmen most disposed to condemn the rising must have been led to hesitate when they saw its apparent spiritual fruits "“ the huge crowds at Masses for the executed leaders, stimulated no doubt, by the widely reported Christian piety and fortitude with which they had met their deaths."

The old order of acquiescence to colonial rule with longterm hopes for political change through negotiation no longer seemed convincing or viable. The successive political events of the anticonscription campaign, the general election victory for Sinn Fein in 1918, and the setting up of Dail Eireann (the Irish Parliament) in 1919 were incremental steps in the process. They led inexorably to a renewed struggle between 1919 and 1921, this time in the form of a guerilla war, which was made possible by popular support.

Nationalism and Missionary Fervor

Early Columban missionaries were inspired by the sacrifice of the leaders of the 1916 rising. Fr. John Heneghan was so moved after hearing the confessions of the Tuam Volunteers on their way to join in the rising that he told a friend with tears in his admiring eyes, "If these brave lads are ready to die for Ireland, I, a priest, ought to be ready to die for Christ." Heneghan joined the new mission as soon as it was launched six months later.

The Maynooth Mission to China avoided publicly taking sides in the nationalist politics of the day in their contact with the clergy while on their parish appeals for funds. But Fr. John Blowick is on record as saying, "I am strongly of the opinion that the rising of 1916 helped our work indirectly. I know for a fact that many of the young people of the country had been aroused into a state of heroism and zeal by the rising of 1916 and by the manner in which the leaders met their death. I can affirm this from personal experience. And accordingly, when we put our message before the young people of the country, it fell on soil which was far better prepared to receive it than if there had never been an Easter week."

Self-Sacrifice for Faith

On August 24, 1920, the day after the first group of Columban missionaries, led by Fr. Edward Galvin reached Hanyang, his brother, Michael, was killed in the ambush of a British army contingent in the south of Ireland. The June 1921 issue of The Far East published a story entitled "For God and Country," describing how a poor widow woman desired and prayed "that her little boy James would be a priest and that Johnny would, as a true son, help in the resurrection of his country." Johnny adopted the patriotic ideal, but the story gave prominence to James, who volunteered to be in the first band of missionary priests to leave for China.

The nobility and romance of the ideal of self-sacrifice for faith and fatherland was incorporated and affirmed by the early members of the Maynooth Mission to China but primacy was given to the faith. The spirit of nationalism sweeping Ireland from 1916 onwards inspired them to a similar fervor in offering themselves to the spiritual ideal of missionary commitment for Christ and the Church.